|

| Hattie McDaniel |

There isn't just one Hattie McDaniel. There are many. There is the true woman and there is her screen identity. There is Hattie herself and Hattie the actress. Hattie the workhorse, the pioneer, the scapegoat, the beloved, the hated, the star, the minority, the champion. Mostly, when we look back over the career of this incredible human being, we define her by her most famous role: "Mammy" in Gone with the Wind. Sad but true, this was essentially the part she was left to play onscreen. Even as a rebellious, ambitious, politically minded soldier of fortune-- the true daughter of her Civil War Veteran father, Henry-- for all her grit and determination, for all her tooth and nail, for all of her accomplishments, she more or less remains a slave, a servant, a victim of the uncompromising racist ideologies of her day. Even more startling are the prejudices inflicted upon her not only by the white element but also the black. A rock in a hard place, she held firmly to who she was and what she believed, her life an eternal struggle to make her mark without apology.

Hattie was the youngest of thirteen siblings, only 7 of whom survived. Born into an impoverished family-- an unfortunate side effect not only of her color but of her father's brave injuries suffered during the war, which rendered him unable to work for the latter part of his life-- Hattie matured quickly. Seeing her father suffer and work through his pain, witnessing her mother's toil to care for her family, she knew hunger, the fight a person had to have to survive let alone prosper, and the importance of an honest, hard day's work. She also learned integrity, and she would walk tall, her head held high in the pride of her roots, her family, and her soul.

|

| Hattie at sixteen. |

She and many of her siblings, all mixtures of pragmatism and artistry, would find a place for themselves on the stage, particularly her brothers Otis and Sam and her sister Etta. Otis was the true standout initially, but after his premature passing, Hattie became the real trailblazer, thought it would take time for her to prove it. Coming from a family of storytellers, singers, and dancers, Hattie eschewed practicality to pursue a career in vaudeville, juggling odd jobs as housekeepers, cooks, etc, to pay the bills. She built a fine reputation on the stage, writing and performing her own blues songs and comedic plays. In the performances of her youth, she would often cleverly thumb her nose at society, her sensual, bawdy humor mocking the white black-face performers of the era and their wide, eye-rolling ignorance. Her intelligence and wit made her a fan favorite, be it in her home state of Colorado (she was born in KS) and anywhere else she traveled. After her husband, piano player Howard Hickman, sadly passed away from pneumonia, Hattie was on her own again. Soon enough, she was bound for Hollywood to meet up with Etta and Sam. She never looked back. (*Hattie would marry thrice more, but all ended in divorce. Howard was the love of her life).

|

| In Show Boat with the very admiring and admirable Paul Robeson. |

The beginning of Hattie's career included the standard bit parts that most film actors endure in the hopes of reaching the top. Yet, Hattie managed to catch enough attention for her double whammy of utter professionalism and characterization to be the metaphorical cream that rises. What set Hattie apart was her defiance. While she was expectantly forced to camouflage her intelligence and adapt to the cliched speech patterns of the "dumb negro," she still managed to inject enough personality and street smarts to make her brief appearances truly memorable. One of her first major coups was her role as the suspicious maid "Cora" opposite Marlene Dietrich in Blonde Venus. Her "I'm no fool" deliveries and unashamed bellowing counteracted the stereotypes placed before her, and better still she somehow maintained an edge of humor so that audiences would be enchanted by her brassy, dynamic characters but not threatened. An example of her cleverness can be seen in her performance opposite Jean Harlow and Clark Gable (the latter of whom was to remain a lifelong fan and friend) in China Seas. In this film, her deliveries opposite Jean identified her as less servant and more gal pal, which gave her onscreen identity more depth than mere "employee."

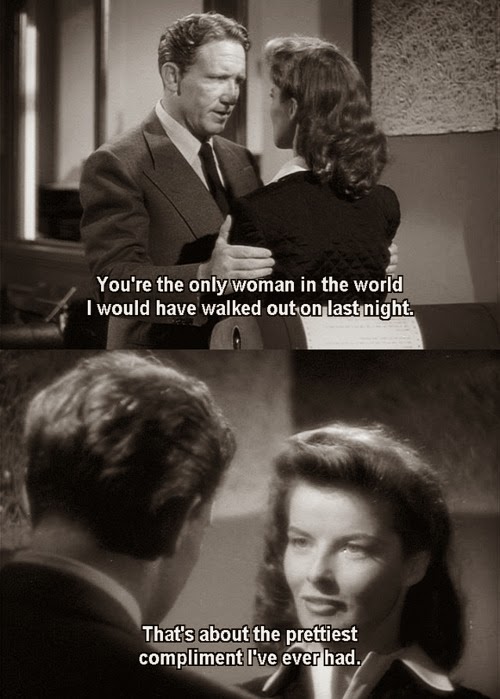

Her turn as the totally uncooperative and flat-out disinterested maid in George Stevens's Alice Adams even stole a major scene right out from under the incomparable Katharine Hepburn. Hattie's lazy stare and irreverence mixed with Stevens's always impeccable sense of timing make the moment a cinematic treasure. Thus, while she was obedient always in her roles, she gave her characters enough independence to show that her loyalty derived not so much from her devotion to her employers but from the pure need to make a living. This made her somewhat of a hero in the industry, and led to her becoming the most successful black star in Hollywood, surpassing even the flagging career of the iconic "slow-witted negro" prototype of early cinema, Stepin Fetchit, who was the first African American, cinematic celebrity. Hattie's performance in the musical Show Boat didn't hurt her reputation either.

|

Hattie proves to be a less than stellar cook and server, smacking her gum

as she haphazardly sets down dinner plates for Fred MacMurray and

Katharine Hepburn in Alice Adams. |

And then came Gone with the Wind, which stirred up a great deal of controversy in its own time let alone in the years to come. Looking back on the film now, some identify it solely for its faults in perpetuating and confusing the African American image on film. Much had to be censored and cut out of the film, including the word "nigger," which it is believed Hattie herself insisted be demolished. Margaret Mitchell devotees couldn't wait to be swept up in the magic of her romantic story being brought to life, while the black and more liberal element was frustrated by the film's fairy tale depiction of the "happy slave," which condoned certain public reactions to and misconceptions of race. Finally, after much political wrangling, the film was made and was a success on all counts. Under the incredible, riveting and authentic direction of Victor Fleming (and George Cukor), the film was epic. The definition of a "sweeping narrative," the incredible story of love in and out of wartime was delivered superbly by Vivien Leigh, Clark Gable, Olivia de Havilland, Leslie Howard, Butterfly McQueen, Thomas Mitchell and of course Hattie McDaniel who all arguably gave the best performances of their careers. Hattie's no-bull sh*t approach to the house slave "Mammy" would bring to life a character that had been much less pushy and much less interesting on the page. Perhaps of all the characters in the film, Mammy is the toughest, as well as the one that no one in his right mind would want to mess with! Of course, it was her gut-wrenching, tearfully panicked scene on the staircase leading "Ms. Melly" to the grieving "Rhett Butler" that won Hattie McDaniel her Oscar-- the first ever earned by an African American.

The film was not altogether rewarding. Hattie wasn't even able to attend the film's Atlanta premiere due to her skin color, and afterward she still had to combat type-casting, which did not improve after her groundbreaking performance. In fact, her career, while comparatively steady, declined in terms of artistry. Hollywood quite simply still didn't know what to do with a "black star." She would still have some bright spots, her proudest cinematic moment being her performance in the provocative and conscientious masterpiece In This Our Life, and her continuing appearance opposite Hollywood's major stars kept her in the spotlight-- The Great Lie, George Washington Slept Here, Thank Your Lucky Stars, Saratoga, and, of course, the very controversial Song of the South, for which her co-star James Baskett won a special Academy Award for his performance as the lovable "Uncle Remus."

|

Hattie and Clark in GWTW. Gable adored Hattie and always attended her private

parties, regardless of public opinion, which led to other whites attending.

What was good for the King was good for everyone else. |

Yet, the major issue was one that had been simmering for awhile. Hattie was attacked by many people in the African American community for her performances in these stereotyped roles. Her existence started to feel like a trap with no escape. On the one hand, she was being held down by an industry that fortunately provided her source of income yet refused to allow her any form of true artistic elevation. On the other hand, she was being crucified by her contemporaries for being a traitor to her race, and as they saw it essentially accepting hush money: shut up and act. Hollywood was not ready for any envelope pushing in the race department-- they had ticket sales to think about. Christian groups and animosity particularly that from Southern theaters and theater-goers made it impossible for filmmakers to be too groundbreaking in terms of unpacking the race issue onscreen. Any who were so bold, generally had their films edited and cut to shreds before they could reach any possibly disgruntled viewers. On one side were veterans like Hattie, Louise Beavers, and Clarence Muse, who believed that their contributions to cinema, while imperfect, were paving the way toward equality in cinema. On the other side, there were the more activist performers like Fredi Washington and the whole NAACP who were dedicated to eradicating racism and believed that all black performers should go on strike until they were given justifiable roles. The tightrope became too difficult for Hollywood to walk, so... they simply stopped. After introducing Lena Horne as the answer to all their problems-- a beautiful, talented, and light-skinned African American leading lady-- they stopped producing politically minded films that even addressed segregation or racial tension and, for a time, cut the black community out of cinema almost entirely.

Roles became scarce, and Hattie found herself without a studio and yet again looking for work--freelancing as she had in her youth. Fortunately, with her impressive resume and popular name, she was able to work, mostly on radio, where her show "Beulah" gained enough notoriety to be produced into a Television show. As ever in her life, Hattie just wanted to work. It was who she was, and she knew no other way. Her steam engine of positivity and unstoppable work ethic would make it to the age of 60 before diabetes and breast cancer finally claimed her life. Sadly, sixty years of struggle ended with the final insult-- she was refused burial at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery-- where there was segregation even in death (see past article here).

|

Hattie rarely got to unwind and clown it up like she once

did on stage, but you can see some of her comedienne

spirit peeking out here. |

Though many have "forgiven" Hattie for her performances, which are often read as nothing more than examples of man's bigotry, her talent and personal character seem to have survived all critical tongue lashings. Many modern industry icons, like Spike Lee, speak out in her defense, paying their respects to a woman who endured so much in order to make the road for those to follow a little easier to tread. While America can't help but still enclose the beloved protector Mammy to their hearts, an act that I would like to believe is done out of true adoration for the woman who created her, few are aware of all that very special woman was. Hattie was eloquently spoken, sophisticated, and always classily dressed. She was kind and loving, donating much of her money and spare time to charities and fundraisers-- particularly to children and education-- and taking care of her family members. A soft touch, she generally donated to anyone for anything. Her intelligence and her great will can be witnessed on the screen in her still remarkable performances, which earned her many admirers among her fellow actors and directors. Today, while her roles still may be attacked, Hattie should not. She never saw the role. She saw only the opportunity to build upon it-- to make her own statement, her own way, on her own terms. The testament to her ability is perhaps that she remains so inseparable from her creations. Just as in her vaudeville days, Hattie pulls the wool over our eyes, teaching us right from wrong, pointing out social inadequacies, and touching our hearts without us even realizing it. Silent instruction: that was her rebellion, but perhaps she said it best:

Trained upon pain and punishment/

I've groped my way through the night,/

but the flag still flies from my tent,/

and I've only begun to fight.

_02.jpg)

_07.jpg)